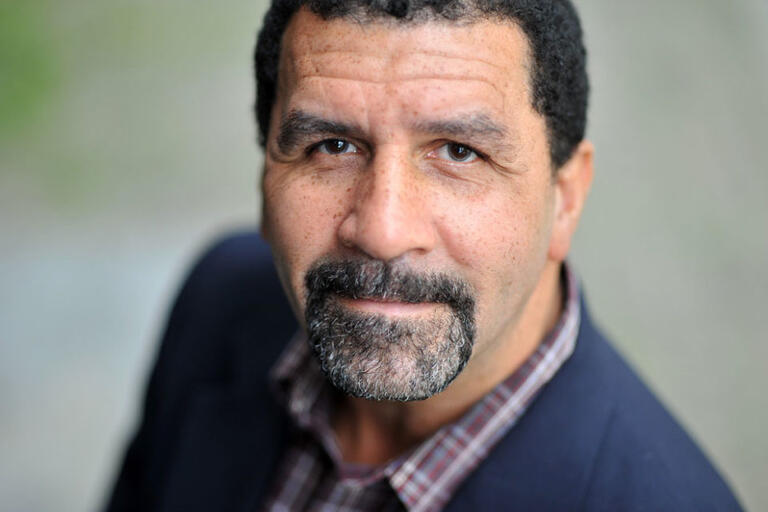

Stephen Small, African American Studies professor, speaks about his book, In the Shadows of the Big House.

In this interview, Stephen Small shares the inspirations behind In the Shadows of the Big House, a compelling and deeply researched work that examines the representation of slavery in contemporary heritage tourism. Drawing from decades of scholarly inquiry and on-the-ground research at plantation sites across the American South, Small investigates the ways in which histories of enslaved people are remembered, erased, or contested in public memory. With a particular focus on Oakland Plantation, Magnolia Plantation Complex, and Melrose Plantation in Louisiana, the book interrogates the intersections of race, tourism, and historical narrative. Small discusses his research process, the enduring legacies of slavery, and the role of plantation museums in shaping public understanding of the past, offering a thought-provoking exploration of how history is told—and who gets to tell it.