Deans maintain heavy workloads and busy calendars, so colleges tend to excuse them from teaching.

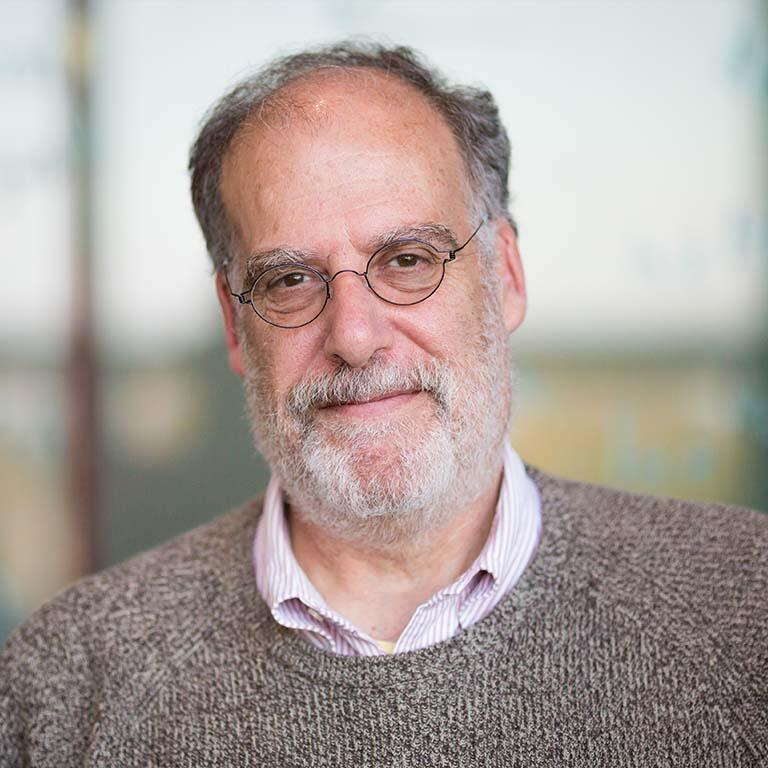

At UC Berkeley’s College of Letters & Science, however, two deans increased their course load this year. Steven Kahn, head of the Division of Mathematical & Physical Sciences, is currently teaching a cosmology course following a fall Freshman Seminar on big science experiments. Dean Richard Harland of the Division of Biological Sciences takes breaks from supervising researchers in his lab to teach developmental biology.

The deans sat down together with UC Berkeley writer Alexander Rony for a conversation on their approaches to teaching, research, and modern educational challenges.