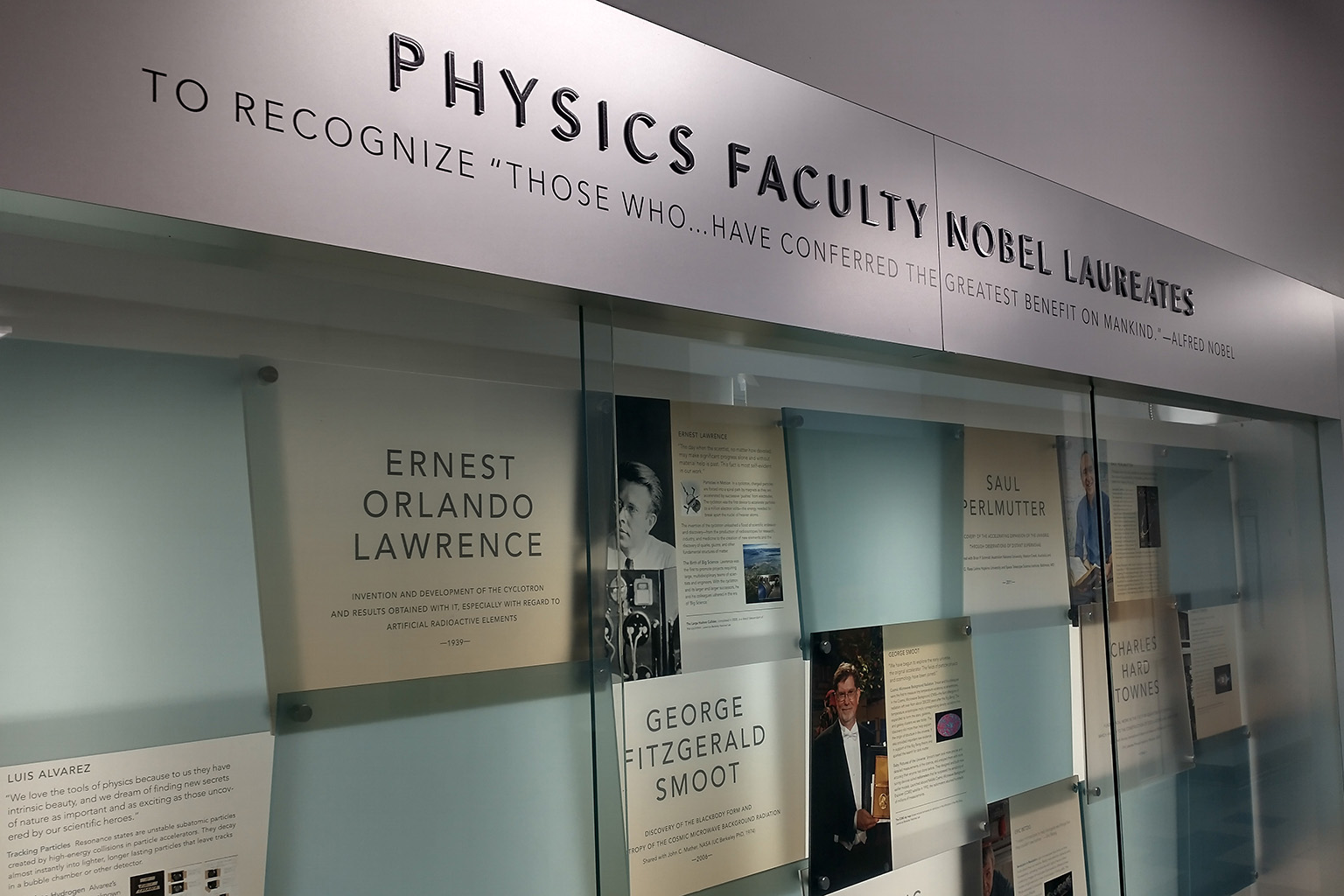

For Irfan Siddiqi, becoming chair of the Department of Physics is about giving back. Since his arrival at UC Berkeley in 2006, Siddiqi has enjoyed the opportunity to teach, write a quantum textbook, and work with stellar graduate students in his lab. Now, he is helping the department plan how to build the “labs of the future” to advance education and research with modern tools.

Globally recognized as an expert in quantum mechanics, Siddiqi specializes in electronic circuits made of superconducting materials that work at ultra-low temperatures within a fraction of absolute zero. His lab produces extremely small circuits — about the size of fifty nanometers, or fifty billionths of a meter — that are critical components in the dilution refrigerators that enable quantum computing. Siddiqi keeps an old, hand-built cryo-refrigerator outside his Quantum Nanoelectronics Laboratory as a reminder of how far the quantum mechanics field has come.

Siddiqi sat down for an interview to share his appreciation and priorities for the physics department.